Eight old fighters arrived at a small, half-empty arena in Denver on November 12, 1993, to take part in a new competition called Ultimate Fighting Championship. A veteran Hollywood director was brought in to make the action look brutal, and he suggested an octagonal cage fenced with chain link.

The organizers stumped up a $50,000 prize pool and told the fighters that no holds were barred. Fake bouts featuring WWF stars like Hulk Hogan and Shawn Michaels dominated the airwaves at the time, and both the combatants and the crowd were skeptical about the prospect of a superior street fight taking place while the TV cameras rolled.

That skepticism was quickly dispelled. The first men into the Octagon were Dutch martial artist Gerard Gordeau and Hawaiian sumo wrestler Teila Tuli. Within 20 seconds, Tuli had tumbled against the side of the cage following a grapple. Before he could climb to his feet, Gordeau kicked him in the face, sending Tuli’s tooth flying into the crowd, where it narrowly missed co-commentator, Kathy Long.

A Golden Dawn

That moment kick-started a martial arts revolution. Gordeau would make it through to the final, where he came up against Brazilian jiu-jitsu star Royce Gracie, who had already defeated Golden Gloves middleweight champion Art Jimmerson and pro wrestling legend Ken Shamrock thanks to his submission wizardry. Gracie dispatched Gordeau with a rear-naked choke after a minute and 44 seconds, seizing the prize.

Word spread of the brutality, electric atmosphere and thrilling clash of styles at UFC 1, and the organizers – Art Davie and Rorion Gracie – decided to launch a second event. “That show was only supposed to be a one-off,” said Dana White, who eventually became UFC president. “It did so well on pay-per-view they decided to do another, and another. Never in a million years did these guys think they were creating a sport.”

They hosted four more events, which showcased an exciting range of fighting styles. There were no weight classes, resulting in some outlandish clashes: 5ft 11ins fighter Keith Hackney, who weighed 200 lbs, took on the 6ft 7ins, 600 lbs giant Emmanuel Yarbrough and won. It was exciting but amateurish.

Challenges Abound

Davie and Gracie sold their interest in UFC to the Semaphore Entertainment Group in 1995, just in time for the backlash to begin. Prominent Senator John McCain led the public outcry after watching footage of UFC and branding it “human cockfighting.” Most states enacted laws that banned no-holds-barred fighting, including New York the day before it was due to host UFC 12, forcing a relocation to Alabama.

Tournament organizers responded to the criticism by overhauling its rules. Fish-hooking was banned, gloves became mandatory, hair-pulling was limited, strikes to the back of the neck and head were outlawed, and then groin strikes and headbutting were prohibited. The most significant change saw a ban on kicking a downed opponent, although it was naturally too late for Tuli’s tooth.

Gradually UFC morphed from a street fight into a sport. By 2001, SEG was on the verge of bankruptcy, and it sold UFC to casino executives Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta and their business partner, White, for $2 million.

Growing Popularity

It remained a niche pursuit, but it grew in popularity under the stewardship of Zuffa, the parent entity created by White and the Fertittas. They made it more professional over the years, introducing corporate sponsorship, pay-per-view sales, and home DVD releases.

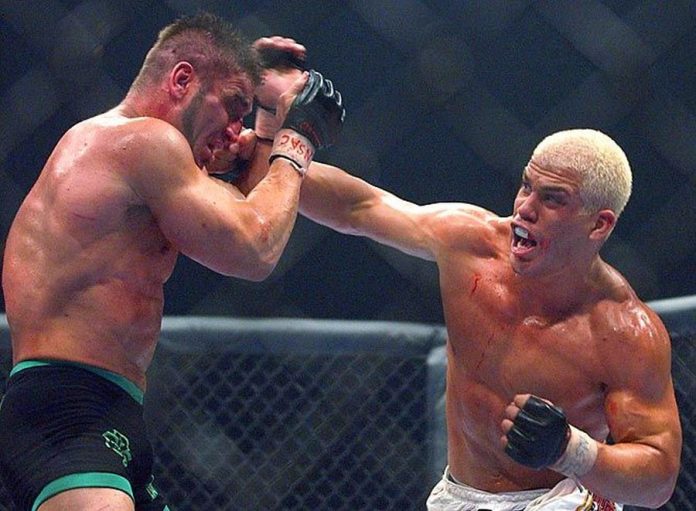

UFC 40 was held at a packed MGM Grand in Las Vegas in November 2002, and it proved to be a landmark event.

The main bout pitted Shamrock against Tito Ortiz, who won via a third-round corner stoppage. It sold 150,000 pay-per-view tickets, more than double the amount sold for a previous UFC event, leading veteran referee John McCarthy to declare it a tipping point.

“When that show happened, I honestly felt like it was going to make it,” he said. “Throughout the years, things were happening, and everything always looked bleak. But, when I was standing in the Octagon at UFC 40, the energy of that fight, it was phenomenal, and it was the first time I honestly said, ‘it’s going to make it.”

A Sporting Behemoth

Yet it still faced losses of $34 million, so UFC made a foray into TV. It launched a reality show called The Ultimate Fighter, which featured up-and-coming MMA fighters bidding to win a six-figure UFC contract.

It proved remarkably popular. That increased UFC’s visibility and pay-per-view numbers skyrocketed throughout the 2000s. Legends like Chuck Liddell rose to the fore, and by 2006, UFC generated annual revenue of $223 million, which saw it exceed both WWE and boxing.

The rest is history. UFC spent the ensuing decade buying up all of its rivals, and it evolved into a sporting powerhouse. It is now established as one of the biggest sports in the world, and if you check out the UFC spread betting options on websites such as Sportingindex.com, you will see how many significant events take place weekly.

It has yielded superstars like Conor McGregor, Ronda Rousey, Nate Diaz, Jon Jones, Holly Holm, Amanda Nunes, Daniel Cormier, and many more. In 2016, Endeavor Group Holdings bought it for $4 billion. It now has more Instagram followers than the NFL, and it boasts millions of fans around the world.

McGregor earned a reported $5 million for his 13-second knockout of Donald Cerrone at UFC 246 last month, showing just how far UFC had come since that fateful evening in Denver 27 years ago. It looks well-positioned for future growth, and it is likely to remain one of the world’s most popular sports in the decades ahead.